The first good travel book I ever read was Paul Theroux’s “The Old Patagonian Express.” Like most good traveler’s tales, the conceit is a simple one: Our narrator hops on branch-line train outside of Boston with intentions of traveling as far as he can. Theroux writes, “My object was to take the train that everyone took to work , and then to keep going, changing trains, to the end of the line. And (consulting a map) this I took to be a tiny station called Esquel, in the middle of Patagonia.”

Patagonia holds a special place in the hearts of the restless, for it is the ultimate end-point in this world of ours. When our ancestors wandered out of Africa some 100,000 years ago (exact dates depend on the archeologist your referencing), they had quite the trek ahead of them. 80,000-60,000 years ago they walked into Asia; 45,000 years ago we sailed the Pacific to establish ourselves in Papua New Guinea and Australia. We entered Europe around 40,000 years ago and didn’t cross into North America until about 15,000 years ago. It wasn’t until about 10,000-12,000 years ago – coincidentally, around the same time that people in the middle east were putting a halt to the migratory patterns of a hunter-gather lifestyle in favor of the stability of settled agriculture – that we reached the end of the habitable world: Patagonia. The southern tip of South America was the terminus of humanities’ great migration, from the comfortable womb of our birth to the wind-scoured edge of our physical adaptability.

Not like we ever stopped wandering once we ran out of earth though. We just had to start manufacturing reasons to move. Nowadays (you know, the past 1,000 years or so) scientific inquiry and monetary gain seem the most common reasons for undertaking a far-flung journey. I suspect the oft-mentioned “finding oneself” is up there as well, though anyone who needs to travel to the ends of the earth to learn who they are probably has more issues than a rail car or even a sail boat is equipped to deal with. But perhaps my favorite journey justification is Bruce Chatwin’s, who traces his desire to visit Patagonia to “ a piece of brontosaurus” that inflamed his imagination from his grandmother’s curio cabinet. Turns out that the Brontosaurus was actually a petrified piece of skin from a Mylodon – a 400lb, 10 foot tall ground sloth native to Patagonia that went extinct right around the time that humans were populating the region.

Not like we ever stopped wandering once we ran out of earth though. We just had to start manufacturing reasons to move. Nowadays (you know, the past 1,000 years or so) scientific inquiry and monetary gain seem the most common reasons for undertaking a far-flung journey. I suspect the oft-mentioned “finding oneself” is up there as well, though anyone who needs to travel to the ends of the earth to learn who they are probably has more issues than a rail car or even a sail boat is equipped to deal with. But perhaps my favorite journey justification is Bruce Chatwin’s, who traces his desire to visit Patagonia to “ a piece of brontosaurus” that inflamed his imagination from his grandmother’s curio cabinet. Turns out that the Brontosaurus was actually a petrified piece of skin from a Mylodon – a 400lb, 10 foot tall ground sloth native to Patagonia that went extinct right around the time that humans were populating the region.

Of course, Chatwin had as good an eye for the dramatic as anyone, and Patagonia is a treasure trove for those looking for good stories. “In Patagonia” is jammed packed with them. There’s the tale of Charley Milward, Chatwin’s cousin, who collected the “piece of brontosaurus” when he settled to Patagonia after sinking the steamer he captained along the Chilean side of the straight of Magellan. There’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, who retired to Patagonia after the heat from their North American pillaging became to much to bear. I use retired loosely, for they while they set up a sheep and horse ranching operation in Cholila at the base of the Andes, they continued to raid banks across the Argentine frontier throughout the early 1900’s. They disappeared again when the Pinkerton Company came looking for them, eventually winding up dead at the hands of the Bolivian Army in 1908. Or so the story goes.

Patagonian history is as shifting and unpredictable as the winds that criss-cross the region. Perhaps that’s because it’s long been a refuge for drifters, outlaws, criminals, and kooks. Not surprising really. A common explanation for the generally craziness in Alaska is that throughout history all the wildest folk headed west before eventually running out of room at the Pacific Coast, when that got too settled they decided to head north. I suspect just as many headed south.

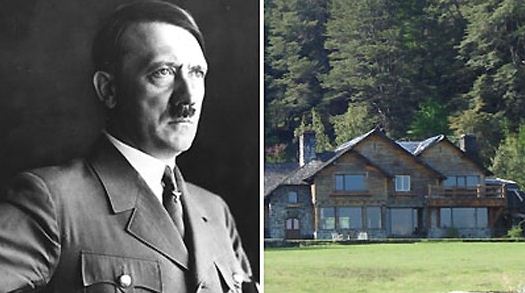

In the 1940’s, as Europe was recovering from the ravages of WWII, Juan Peron, Argentina’s populist president helped turn the country into something of a haven for Nazi war criminals seeking to escape prosecution. Big name war criminals wound up fleeing for Argentina. Before he was captured, and tried in Jerusalem, Adolf Eichmann spent time working at a Mercedes Benz factory in the suburbs of Buenos Aires. There’s even a whole community of conspiracy theorists who claim that Hitler and Eva Braun didn’t die in a Berlin bunker, but rather escaped to live out their days at a chalet in the Andes resort town of Bariloche. Facts or not, truth is that Patagonia is a grand place to base a story.

In the 1940’s, as Europe was recovering from the ravages of WWII, Juan Peron, Argentina’s populist president helped turn the country into something of a haven for Nazi war criminals seeking to escape prosecution. Big name war criminals wound up fleeing for Argentina. Before he was captured, and tried in Jerusalem, Adolf Eichmann spent time working at a Mercedes Benz factory in the suburbs of Buenos Aires. There’s even a whole community of conspiracy theorists who claim that Hitler and Eva Braun didn’t die in a Berlin bunker, but rather escaped to live out their days at a chalet in the Andes resort town of Bariloche. Facts or not, truth is that Patagonia is a grand place to base a story.

And Patagonia is home to a wide range of immigrant populations of a much less nefarious provenance. Sizeable numbers of Germans, Welsh, Scottish , and Italians have been drawn to the land at the end of the earth. It's one of those places that has a special pull in the hearts of the restless, hopefully one strong enough to carry us over the Andes!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed