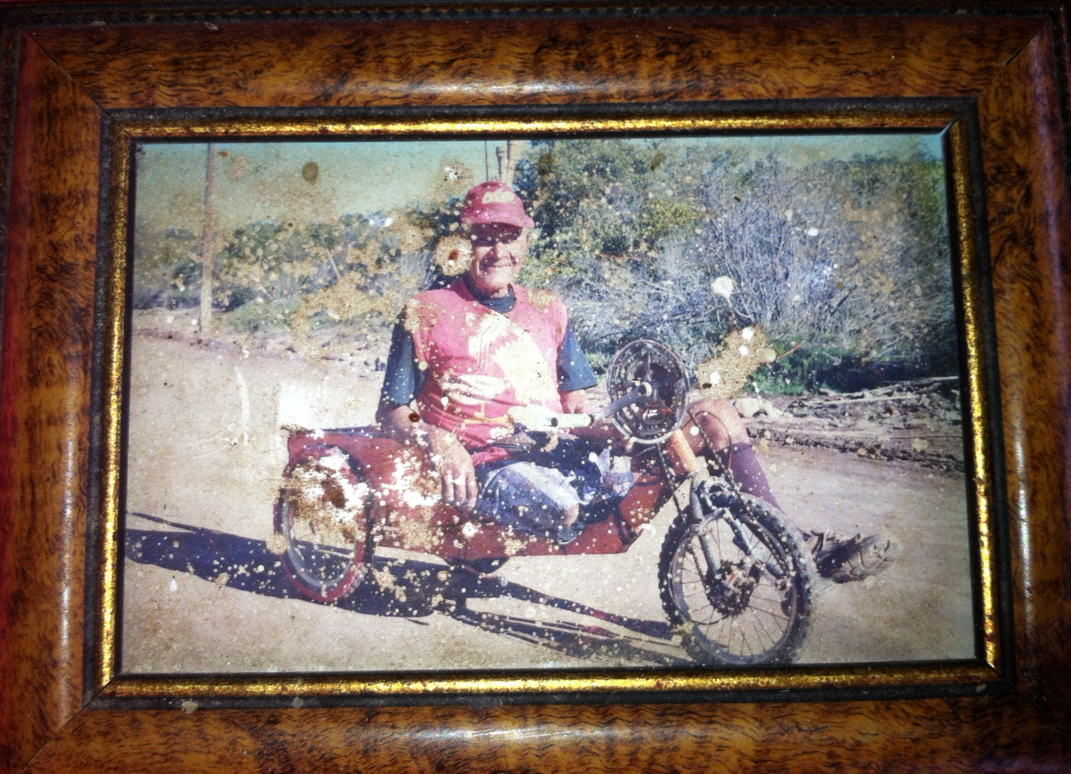

When Alejandro Bukovecz speaks of his father, Antulio, his eyes glow and an irrespresable grin spreads over his face. It's the same grin in the weathered photo he has placed on the table for us to see. In the photo, the grin is framed by wrinkly cheeks, sun-browned to the color of tanned leather. The eyes are shaded by a baseball cap but still squint against the bright light of a Baja afternoon. "He was always smiling," Alejandro says. "That's just how he was, no matter how he was doing, or how hard things were, he always had the same smile on his face."

Looking beyond the smile, Anutulio sits atop a boxy metal frame painted orange. The orange steel extends in front of him to a headtube that attaches a bicycle crank assembly, chain, and 20" front wheel with a knobby tire. A stringy leg straddles one side of the wheel, and on the other, a fleshy stump rests just behind the edge of his shorts.

Anutulio was a life-long bicyclist and racer before he was in a car accident out in the desert near Cataviña. Losing one leg and most of the function in the other, Antulio languished in the hospital. "I'll never forget the first time I saw him after the accident," Alejandro says. "He was sitting in his hospital room looking out the window and he looked like a bird in a cage. He looked so sad! Like all of the life had been drained out of him. I mean his skin looked yellow! He says to me, 'I need you to talk to a welder. I have an idea for a tricycle.'"

I smile as Alejandro shakes his head in wonder. It's a mindset that I can identify with. For an active person, a debilitating accident leaves you feeling like the foundation of your life has been suddenly stripped away. Your most fundamental connection to the world, the ability to move through it, has been severed. At that point, there are only two real options - to despair or to figure out new ways of moving. Antulio decided to get moving again.

So he began designing, and with Alejandro's help, fabricating his own handcycles. I suppose no one told him what he could or couldn't do now that he had a disability, or perhaps more likely, he was too stubborn to listen. But Antulio started riding his new bike like he had before - 100 kilometers a day, often riding 8 days from Mulegé to Ensenada, then back again. Anutulio toured without calling it touring, he was simply going for rides and they took him across Mexico. With a modicum of tools and supplies strapped to the back of his bike he would ride, for days, weeks at a time. Sleeping behind roadside bushes, underneath highway bridges on sandy arroyos, he lay wherever he needed to.

One time, he had ridden all the way across Mexico, and was passing through Veracruz when a big para-cycling race was about to take place. Antulio had raced before his accident and decided to try it again. Riding his homemade trike, with his tools and gear still strapped to the back, he finished second in his classification behind Mexico's reigning national champion. Antulio figured he could have beat everyone if he hadn't had to change his own tire mid-race. "That was fun," Antulio told the champion. "I'll come back next year and beat you."

And he did. Antulio, the wrinkled man in his 60's, won the event for the next few years. The former champion complained that Antulio had too many gears in his handcycle. "Next year I'll bring another bike, you can race in that, and I'll still beat you," Antulio responded.

We show Alejandro my handcycle and he revels in the similarities to the bikes he helped his dad build, marvels at the fancy new materials. Alejandro ask how far we're going."Argentina," I say.

He puffs his breath out in a silent whistle. "That's great," he says. "The farthest my dad made it was to the border with Guatemala. He always wanted to go all the way down there, but we'd tell him, 'No, no. It's too far, it's too dangerous. '" For the first time since he started talking about his dad, a brief look of sadness, or maybe remorse, passes over his face. "But I think he could have done it."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed