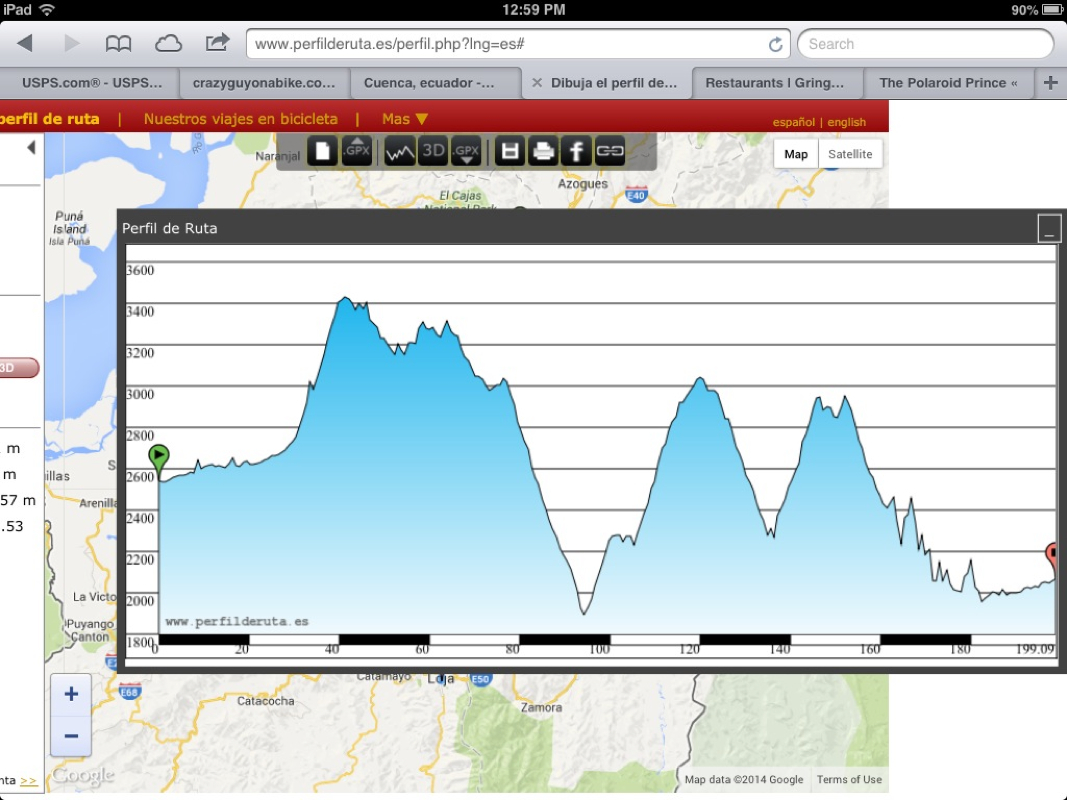

Hello from Loja, our final resting spot in Ecuador. Our trip from Cuenca proved to be as challenging as we thought. We had a few short days with huge mountains to climb and camped out in the rain quite a bit. Seth got sick again (luckily we were already in a hotel), and we ended up thumbing a ride to Loja.

Here are a few pictures from our last leg of the journey.

Sorry for the short post -- not a lot has happened, but figured it'd be good for people to know our status. Tomorrow, Wednesday, we board a bus for Piura, Peru. Then we'll bus through the coastal heat to Trujillo, where we'll be meeting up with a good friend -- Jared. He's coming with a fresh attitude and food from home. We can't be more exited -- friend, food, and a new country!!

Also, an article was just published in Women's Adventure Magazine, written by Dana McMahan (thank you, Dana!). She did a story on Kelly, you can check it out here:

https://s3.amazonaws.com/external_clips/565327/portlandtopatagonia.pdf?1393869376

RSS Feed

RSS Feed